THOUGHTS: 2020

Spillover effects from voluntary employer minimum wages

Ellora Derenoncourt, Clemens Noelke, and David Weil

SSRN. 2.28.21

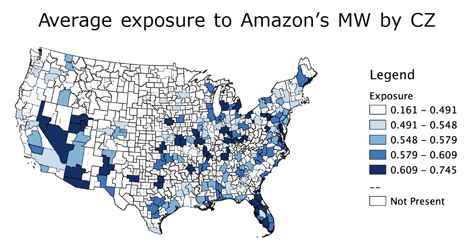

Low unionization rates, a falling real federal minimum wage, and prevalent non-competes characterize low-wage jobs in the United States and contribute to growing inequality. In recent years, a number of private employers have opted to institute or raise company-wide minimum wages for their employees, sometimes in response to public pressure. To what extent do wage-setting changes at major employers spill over to other employers, and what are the labor market effects of these policies? In this paper, we study recent minimum wages by Amazon, Walmart, Target, and Costco using data from millions of online job ads and employee surveys. We document that these policies induced wage increases at low-wage jobs at other employers. In the case of Amazon, which instituted a $15 minimum wage in October 2018, our estimates imply that a 10% increase in Amazon’s advertised hourly wages led to an average increase of 2.6% among other employers in the same commuting zone. Using the CPS, we estimate wage increases in exposed jobs in line with our magnitudes from employee surveys and find that major employer minimum wage policies led to small but precisely estimated declines in employment, with employment elasticities ranging from -.04 to -.13.

Download entire paper.

MORE ON THE SUBJECT: “When Amazon Raises Its Wages Local Companies Follow Suit,” by Ben Casselman and Jim Tankersley, 3.5.21, New York Times. Read article.

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++The future of work… as determined by Uber?

Interview with David Weil by Molly Wood

Marketplace Tech. 11.26.20

As the pandemic recession drags on, people are turning to gig work to fill the gaps, and the nature of that work is evolving. Proposition 22 in California, which passed this month, lets companies classify delivery and ride-hail drivers as independent contractors. There are some new requirements, such as a wage floor and some health benefit options.

As the pandemic recession drags on, people are turning to gig work to fill the gaps, and the nature of that work is evolving. Proposition 22 in California, which passed this month, lets companies classify delivery and ride-hail drivers as independent contractors. There are some new requirements, such as a wage floor and some health benefit options.

Some describe it as a “third way,” between benefit-free part-time work and traditional full-time employment. If the idea catches on more broadly, what could it mean for how we work? I spoke with David Weil, dean at the Heller School for Social Policy and Management at Brandeis University. He told me about the origin of the idea. The following is an edited transcript of our conversation.

David Weil: Well, the third way comes, in fact, from Canada, where there is a concept of what’s called a dependent contractor, where you have a set of protections that are designed for independent contractors that really rely on a single or a small number of major employers who are contracting their business to protect independent contractors who really had this level of dependency. But I think the problem of the third way is the fact that Canada starts in a very different place than workers in this country start.

READ or LISTEN to entire piece.

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

How has the Trump administration changed labor protections?

By David Weil, Oct. 29, 2020

In the run-up to the presidential election, BrandeisNOW asked faculty to provide analysis and insight into some of the most pressing issues facing the country. This is part of the series.

One of the cornerstones of U.S. social policy are basic labor protections that provide for a minimum wage, overtime pay and assurance that people will be paid for the work they do.

These laws are fundamental to addressing the inherent imbalances of bargaining power in labor markets. Assuring that workers receive these protections and exercise their rights requires applying these core workplace statutes in changing times through enforcement, outreach, education and regulatory review.

During the Obama administration, I had the honor of leading the Wage and Hour Division, an agency at the U.S. Department of Labor that enforces minimum wage, overtime, child labor and other basic labor protections. During my tenure, we focused in two areas.

1. We issued regulations and regulatory guidance to expand protections to more workers.

For example, we extended coverage to two million home care workers for the first time; and we updated overtime rules to assure that millions of workers who had fallen out of coverage would once again receive overtime pay for working long hours.

We also issued critical guidance to clarify that these labor standards still apply in increasingly complicated fissured workplaces – that is, business models that are built on outsourced, subcontracted or franchised work, where a lead business controls what workers do, but attempts to distance itself from the responsibilities that come with employment.

2. We increased the number of investigators and took a strategic approach to enforcement to make sure that our limited resources had the largest impact on workers most prone to violations.

Unfortunately, the Trump administration has systematically rolled back progress on both fronts.

The administration revised the overtime rules to reduce the number of workers eligible for overtime pay and modified the definition of an employer in ways that potentially narrow rather than expand protections for workers.

The administration also failed to staff these agencies at levels necessary to assure adequate enforcement and blocked the use of tools that incentivize employers to proactively comply.

In the last month, the administration issued orders across labor agencies to curb public notice of violations of law — even though studies show those notices proactively deter noncompliance.

These steps would have been troubling in normal times, given the rise of economic inequality and eroding labor protections. But the hardships that the COVID-19 pandemic has inflicted on workers — particularly frontline workers who are disproportionately women and people of color — are pushing us even further in the wrong direction.

Many of the Trump administration’s changes are being contested in court and would likely be reversed in a Biden administration.

A new administration might also be expected to focus on rebuilding agency staffs through increased Congressional appropriations, reinvigorating enforcement efforts, particularly in front line industries of the pandemic, and working with Congress to enact key pieces of his policy priorities (including raising the federal minimum wage).

A second term of the Trump administration would mean further reductions in enforcement and further narrowing the scope of those activities to cover only the most egregious violations of workplace laws.

Widening income inequality, further expansion of fissured work and a more precarious workplace would likely arise from the continuation of those policies over four more years.

+++++++++++++++++++++How to determine if a business is COVID-19 safe?

Create a restaurant-style grading system

By Archon Fung, David Weil, and Mary Graham

Op-Ed piece for Los Angeles Times, June 9, 2020

Uncertainty and fear of a virulent pathogen are powerful deterrents to social and economic engagement, in addition to the record levels of post-Great Recession unemployment. Nearly 70% of respondents in a national poll published in early May said they were uncomfortable with the idea of shopping in clothing stores and almost 80% expressed misgivings about eating in restaurants, regardless of government reopening plans.

Uncertainty and fear of a virulent pathogen are powerful deterrents to social and economic engagement, in addition to the record levels of post-Great Recession unemployment. Nearly 70% of respondents in a national poll published in early May said they were uncomfortable with the idea of shopping in clothing stores and almost 80% expressed misgivings about eating in restaurants, regardless of government reopening plans.

To counter this fear and uncertainty, government standards and a ratings system should be put in place.

Governments would need to provide and enforce specific workplace safety and health standards for businesses in different sectors — such as retail establishments, restaurants and personal-service providers — that would protect workers and customers. Those would be followed by a simple ratings system that communicates to workers and customers which businesses are doing their utmost to protect public health and which ones are treating the novel coronavirus lackadaisically.

Public safety begins with worker safety. The Occupational Safety and Health Administration has failed to issue emergency COVID-19 standards. Instead of enforceable and robust standards, OSHA has offered only loose guidance that it acknowledges “creates no new legal obligations.” As of mid-May, OSHA had received more than 13,600 COVID-19-related complaints but had issued no citations or penalties. The result of that laxity has been rapid COVID-19 spread and death in food processing plants, retail outlets and nursing home facilities in the United States.

Massachusetts General Hospital and some other healthcare facilities that have been at the forefront of COVID-19 treatment have developed work processes to limit cross-contamination.

Public health expert recommendations to minimize worker and consumer exposure include screening, contact tracing, physical distancing at work, training to control infection, and ongoing surveillance to detect illness early. But unions, other worker organizations and consumer groups should not have to rely on the goodwill of businesses.

Instead, these groups should participate in the rapid development and implementation of standards to assure that the concerns of working people and the public are adequately addressed. Since the federal OSHA has so far proved unwilling to ensure the adoption of such process standards, state and city public health authorities should do so.

State and local governments could then grade businesses such as restaurants, grocery stores, hair salons, movie theaters and other retail operations. The grades would be based on their adoption of emergency standards and additional measures they’ve taken to fight COVID-19.

Are they following steps outlined for their industry regarding masks, protective equipment, physical distancing, deep cleaning, adequate ventilation, testing, paid sick leave, reporting employee infections, and whistleblower protection for workers who point out deficiencies?

Over five years, we studied rating and grading systems that rank safety and quality in many industries, including restaurants, health care, banking, education and manufacturing. We found that information was most effective when it is provided where people make choices, and in a way that everyone can understand, regardless of education or language skills.

Long-standing public health disclosure systems in Los Angeles County, New York City and many state and local governments have shown the way. Restaurants are required to post in their windows A, B or C grades for hygiene and food safety that are based on unannounced health department inspections. Inspectors lower grades if they find evidence — such as rodent droppings or unwashed greens — that restaurants aren’t doing enough to prevent food poisoning. These report cards have pressed businesses to become cleaner.

Establishing a similar system of COVID-19 safety grades would encourage consumers to shop and eat where workers and the people they serve are protected, thereby helping to control the spread of the disease. It would enable customers and workers to protect themselves by choosing “A” businesses and workplaces and avoiding those with C grades — just like they do with the restaurant ratings.

The market pressure of consumers looking for “A” businesses would probably motivate employers to do what it takes to earn one. COVID-19 workplace safety standards will vary across different industries and evolve as scientific understanding improves. Child-care centers would obviously need to take different steps than grocery stores or restaurants.

Creating this system would require cash-strapped governments to quickly develop grading standards and expand inspection capacity. But the cost of fearful and uncertain consumers and workers who can’t tell which businesses are safe would be much greater. To start, grades could be introduced in stages, with state and local governments that already require standards taking the lead.

Failing grades would go to places that don’t meet emergency COVID-19 standards. Businesses and workplaces that exceed minimum standards and push the envelope on worker safety and public health would earn good A and B grades.

The grading system could inspire a “race to the top” as businesses seek to adopt the very best practices to prevent the spread of COVID-19.

Once restaurant grading was in place, researchers found that food poisoning declined by 13% in just two years. But over time, grade inflation and lax inspections weakened the system in some jurisdictions. Making businesses transparent about their COVID-19 performance will require robust ongoing enforcement with consequences for noncompliance.

By deciding where they eat, shop and work in the coming months, the American people will help restore the country’s economic vitality. Enforced workplace health and safety standards and a COVID-19 grading system would help them reenter society more confidently.

Archon Fung, David Weil and Mary Graham co-direct the Transparency Policy Project at the Harvard Kennedy School and are the authors of “Full Disclosure.” Fung directs the democracy programs at the Ash Center of the Kennedy School and Weil is dean of the Heller School for Social Policy and Management at Brandeis University.

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

Who’s Responsible Here? Establishing Legal Responsibility in the Fissured Workplace

By Tanya Goldman and David Weil

Institute for New Economic Thinking

March, 2020

This article proposes a new “Concentric Circle framework” which would improve workers’ access to civil, labor, and employment rights.

The nature of work is changing, with workers enduring increasingly precarious working conditions without any safety net. In response, this Article proposes a new “Concentric Circle framework” which would improve workers’ access to civil, labor, and employment rights.

Many businesses, including app-based platforms, have restructured toward “fissured workplace” business models. They treat workers like employees (specifying behaviors and closely monitoring outcomes) but they classify workers as independent contractors (engaging them at an arms-length and cutting them off from rights and benefits tied to employment). These arrangements confound legal classifications of “employment” and expose deficiencies with existing workplace protections, which are based on “employment relationships.” As a result, a growing number of workers lack both bargaining power and critical workpalce rights and benefits.

We propose a Concentric Circle framework to better govern workers’ rights in the modern era. At the core, we maintain that certain rights and protections should not be tethered to an employment relationship, but to work itself. Thus, the right to be compensated for work and paid a minimum wage; freedom from discrimination and retaliation; access to a safe working environment, and the right to associate and engage in concerted activity should belong to all workers, not just employees. Second, as a middle circle, we argue for a rebuttable presumption of employment to address those rights that remain exclusive to employees (and not independent contractors), and we propose an updated legal test of employment. Finally, at the outer ring of the framework, we suggest policies that could enhance workers’ access to benefits that promote worker mobility and social welfare.

Other scholarship has focused exclusively on either independent contractors or employees, or it has proposed a new category of worker altogether. We contend that this comprehensive framework better assigns rights, responsibilities, and protections in the modern workplace than do current legal doctrines or alternative proposals.

Download article.